This page may contain one or more affiliate links, which means that if you purchase a product through that link, I may receive compensation. The links will be identified with the text "affiliate link". Click to learn more.

In 1993, Kevin Stokes made what seemed like yet another “Wolfenstein 3D” clone, riding the wave of the popular DOS game that made first-person-shooters popular. However, his game, titled Lethal Tender, was actually creative and unique in many ways with features that other games would adapt later, like Doom or Duke Nukem 3D. Even more interesting is the framework and foundation that Lethal Tender laid down to create its sequel Terminal Terror and, above all, the 3D Game Creation System that would later be sold to consumers.

Early FPS Mechanics That Set Lethal Tender Apart from Its Clones

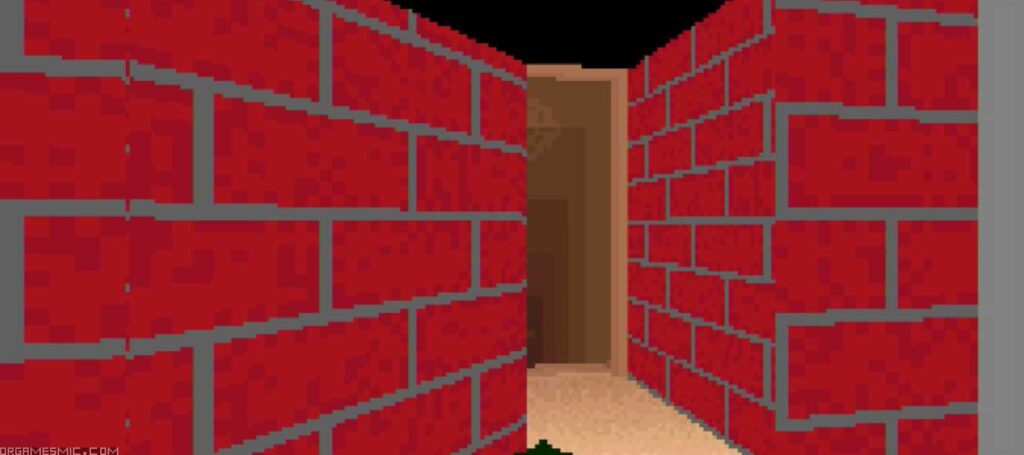

As a product of the first-person-shooter (FPS) copycat boom of 1993, it contains similarities to Wolfenstein 3D, like solid-colored ceilings and floors in order to run faster and smoother on PCs. Lethal Tender also contained two primary enemies wearing different color uniforms, which is something commonly seen in the shareware version of Wolf 3D. (But alas, no dogs.) There is also a pistol, a machine gun, health packs and ammo that can be picked up. From the sound of it, it definitely fits the same type of game genre. However, it’s not what this game has in common with Wolf 3D that is intriguing, but rather the advancements that it lacks.

Jumping in Lethal Tender: A Platforming Element Missing from Doom

Being able to jump in a video game seems like such an obvious concept, doesn’t it? And yet the idea, which today we may call “platforming” didn’t seem to be a contributing factor in FPS up to this point. Lethal Tender contains a point where there is apparently toxic sludge that needs to be dodged by a tactfully planned leap. Seems pretty standard when compared to classic games like Halo, where jumping is a leading feature of the game.

However, even Doom (from 1993) didn’t have this ability. Players had to use the “run” button to move between platforms that were too far apart to walk across. Even the game Heretic, released a year later in 1994, still didn’t have a jump feature. Major strides (no pun intended) weren’t made mainstream until Hexen in 1995 and Duke Nukem 3D in 1996. By then, we finally were able to see something as simple and important as “jumping” begin to hit first-person shooters.

The toxic sludge in Lethal Tender made itself known by its appearance and gave a reason to jump. Rather than being stagnant, it appeared to be moving. This hint of “maybe I shouldn’t be standing there” wouldn’t appear again until Doom. It also created motivation to jump across a raised surface. This in itself was a new puzzle to be solved.

Full-Body Damage Before It Was Cool: Lethal Tender’s Combat Innovation

Classic computer games like Deus Ex stood out and broke ground by having damage to individual limbs that would affect gameplay. In a similar way, Lethal Tender had it so that if you are shot in the leg, it would affect your ability to walk straight.

Although such a feature as damaged limbs may seem obvious for a game genre where you get shot all over the place if it were real life, most FPS skipped over this. Later titles like Fallout 3 would make this a key feature, but the road to this outcome in games was a long one.

Slanted Surfaces and Rooftop Geometry

Remember barreling through Wolfenstein 3D’s rigid, right-angle corridors and feeling like you were inside a giant cardboard box? Lethal Tender quietly slipped in slanted rooftops and angled surfaces (yes, actual rooftops you could walk under). Why care about a tilted roof in a DOS shooter? Because in a sea of flat floors, it hinted at verticality long before true 3D engines let you climb actual stairs.

Technically, Pie in the Sky’s Power 3D engine didn’t support real polygons—but clever texture mapping and level-design hacks faked those slopes. You’d crest a low ridge and suddenly feel like you’d crested something, even if you couldn’t hop onto it like in Halo. That illusion of depth made every courtyard and rooftop feel less like a static arena and more like a real facility you were infiltrating.

Hinged Doors and Spatial Realism in Pre-3D Shooter Environments

Remember barging through those sliding doors in Wolf 3D? Lethal Tender opted for swinging, hinged doors that actually reacted to your push or pull—and sometimes creaked ominously as they opened. This simple addition did more than break the monotony of gray hallways: it created choke points where enemies could lie in wait, and lent a tactile authenticity to facility maps.

Technically, adding door-swing animations meant extra loops of graphics and collision checks—uncommon in 1993 shooters. The payoff was palpable. Suddenly you weren’t just strafing through sterile corridors; you were tactically clearing rooms, keyed in on sound cues, stealth-peeking around doorframes. That interactive immersion was a seed of what modern stealth-FPS hybrids would harvest decades later.

Games like Ken’s Labyrinth had images that looked like swinging doors, but didn’t actually contain them. Duke Nukem 3D did eventually have impressive swinging doors, but had technical issues with them overlapping and killing the player if they were standing in the way.

Early FPS Inventory Systems: Lethal Tender’s Tactical Advantage

Forget Doom’s key-cards. Lethal Tender gave you a bona fide inventory screen. Pick up ID badges, med-kits, ammo belts, even a handful of landmines, and manage them in a minimalist grid. It felt almost survival-horror adjacent, forcing you to weigh “Do I carry another grenade or a spare health pack?”

This blend of FPS immediacy and strategic resource juggling was ahead of its time. Where most DOS shooters shoved every pickup straight into your armory, Stokes’ design slowed you down long enough to consider your next move. We didn’t see any inventory manipulation or management system in many FPS games until Heretic in 1994.

Grenades, Bombs, and Landmines: Explosive Strategy in a ’90s Shooter

While other games like Wolfenstein 3D didn’t have anything at all resembling anything explosive, Lethal Tender went ahead and has throwable grenades, remote-control bombs and landmines. The game even had exploding barrels, something that later (thanks to Doom) would become a staple feature used in seemingly all FPS games. The “splash damage” created from explosions was a game-changer (yes, I said it) since it changed the strategy of how shooters were played.

From Lethal Tender to Terminal Terror and the 3D Game Creation System

Sacrifices had to be made for the upgrades in Terminal Terror. The chopping block included hinged doors and slanted rooftops. But the biggest offender was that each level had only one type of enemy.

That being said, Terminal Terror was a huge upgrade over Lethal Tender. Textured Floors and ceilings, music, better graphics and improved weapons stand out in this sequel.

But the real legacy came when the Power 3D engine was retooled into the 3D Game Creation System, literally handing aspiring designers the keys to build Wolf3D-style worlds with hinged doors, sloped surfaces, and custom hazards.

That democratization of level design sowed the roots of the indie FPS boom decades later. Without Lethal Tender’s engine work, tools like the Build engine (Duke Nukem, Blood) might have taken longer to appear on hobbyists’ hard drives.

Rediscovering the FPS That History Skipped

Lethal Tender wasn’t a blockbuster, but it quietly threaded together jumping, animated hazards, body-specific damage, realistic doors, and tactical inventory before they became genre staples. It’s the perfect case study in how “clones” can innovate under the radar.

So next time you boot up Doom or Duke Nukem 3D, spare a nod for Nick Hunter’s green uniform and those slanted rooftops. Without that little DOS oddity, the history of first-person shooters might look a lot more flat.